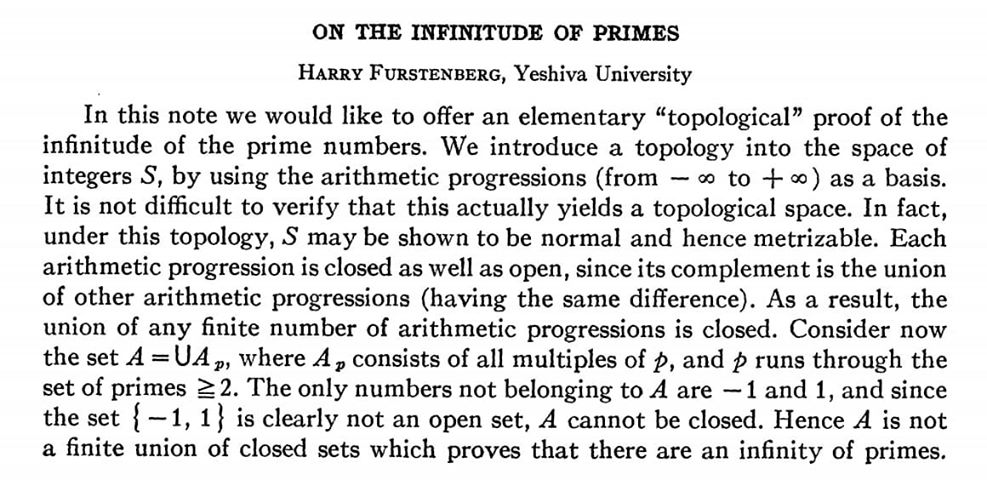

One of the most clever proofs for the infinitude of primes was authored by Hilel Furstenberg. It involves defining a topology on $\mathbb{Z}$, and using some of the properties of that topology to derive a contradiction, which proves that the number of primes cannot be finite.

A little introduction to topologies

A topology is how mathematicians formalize the notion of “open sets”. For instance, in $\mathbb{R}$, we usually call the set $(0,1)$ open because it does not contain its endpoints. Similarly, $[0,1]$ is closed because it does contain its endpoints. This notion of “open” or “closed” can be generalized for any set.

Let $X$ be any set of things; it could be real numbers, integers, vectors, whatever. A topology $\tau$ is a set that contains every subset of $X$ that we would like to call “open”. In other words, a subset of $X$ is called open if and only if it is an element of $\tau$. The topology $\tau$ must satisfy the following axioms:

- Both $\varnothing, X \in \tau$; that is, both $\varnothing$ and $X$ are open.

- Any arbitrary union of sets in $\tau$ is also in $\tau$; that is, if we grab any number of open sets (finite or infinite, countable or uncountable) and then take their union, this union is also open.

- If $A, B \in \tau$, then $A \cap B \in \tau$; that is, the intersection of finitely many open sets is also open.

Why are these axioms necessary? Basically, they capture the essence of how open sets can be combined with each other to produce other open sets. In $\mathbb{R}$, I can take the union of $(0,1)$, $(0, 1.1)$, $(0, 1.11)$, $(0, 1.111)$, and so on, and the result will still be an open set. So no matter how many open sets I choose, their union will still be open. But if I try to take the intersection of $(0, 1.1)$, $(0, 1.01)$, $(0, 1.001)$, $(0, 1.0001)$, and so on, the result will be $(0, 1]$, which is not an open set. So this is why it is necessary to restrict ourselves to just taking the intersection of finitely many sets.

Now, a subset of $X$ can be both closed and open. For example, in $\mathbb{R}$, the set $\mathbb{R}$ itself is considered both closed and open. What makes a set closed is that its complement is open. More precisely, if $A \in \tau$, then $X \setminus A$ is closed.

The proof

Now we are ready to understand Furstenberg’s proof. We will define topology $\tau$ on $\mathbb{Z}$, where every arithmetic progression is considered open. That is, for any integers $a$ and $b$, we have $\{a + bk: k\in \mathbb{Z}\} \in \tau$. Now, it is worth pointing out that $\tau$ contains more than just those arithmetic sequences; it contains unions and intersections between them as well.

Moreover, any such arithmetic sequence in $\tau$ is closed in addition to being open. This is because for any such sequence, its complement is the union of other arithmetic sequences. The proof of this is left as an exercise to the reader.

Let $A_p = \{pk: k\in\mathbb{Z}\}$. It is clear that $A_p\in\tau$ for any given $p$. Now, every integer greater than 1 has at least one prime factor. Hence,

\[\bigcup_{p\,\mathrm{prime}} A_p = \mathbb{Z} \setminus \{1, -1\}\]This is a union of open sets, so $\mathbb{Z} \setminus \{1, -1\}$ is also open. But let us now examine the complement of this union, which we can obtain using De Morgan’s laws:

\[\bigcap_{p\,\mathrm{prime}} \mathbb{Z}\setminus A_p = \{1, -1\}\]Since we mentioned earlier that arithmetic sequences were both closed and open, that means that each $\mathbb{Z}\setminus A_p$ is open. And we are taking the intersection of many of these $A_p$.

Now comes the crucial step: If there were only finitely many primes, then we would be taking a finite intersection of open sets, which would mean that the result is an element of $\tau$. But clearly $\{1, -1\}\notin \tau$, because there is no amount of unions or intersections of arithmetic sequences that we can make that would result in $\{1, -1\}$. So we conclude that the number of primes must be infinite.